Synthetic data in pricing

How use of synthetic data will change pricing

Synthetic data in pricing series

Synthetic data in pricing: How use of synthetic data will change pricing

Risks with synthetic data in pricing: Don’t get lost in the data

Use cases for synthetic data in pricing: where to use synthetic data

TL;DR (Too Long; Didn’t Read)

Use of synthetic data is becoming standard in pricing, enabling richer experiments, more accurate predictions, and large‑scale simulations across scenarios and segments.

Generative AI makes synthetic data both necessary and practical by expanding the solution space (more offers, configurations, models) while slashing the cost and latency of pricing analysis.

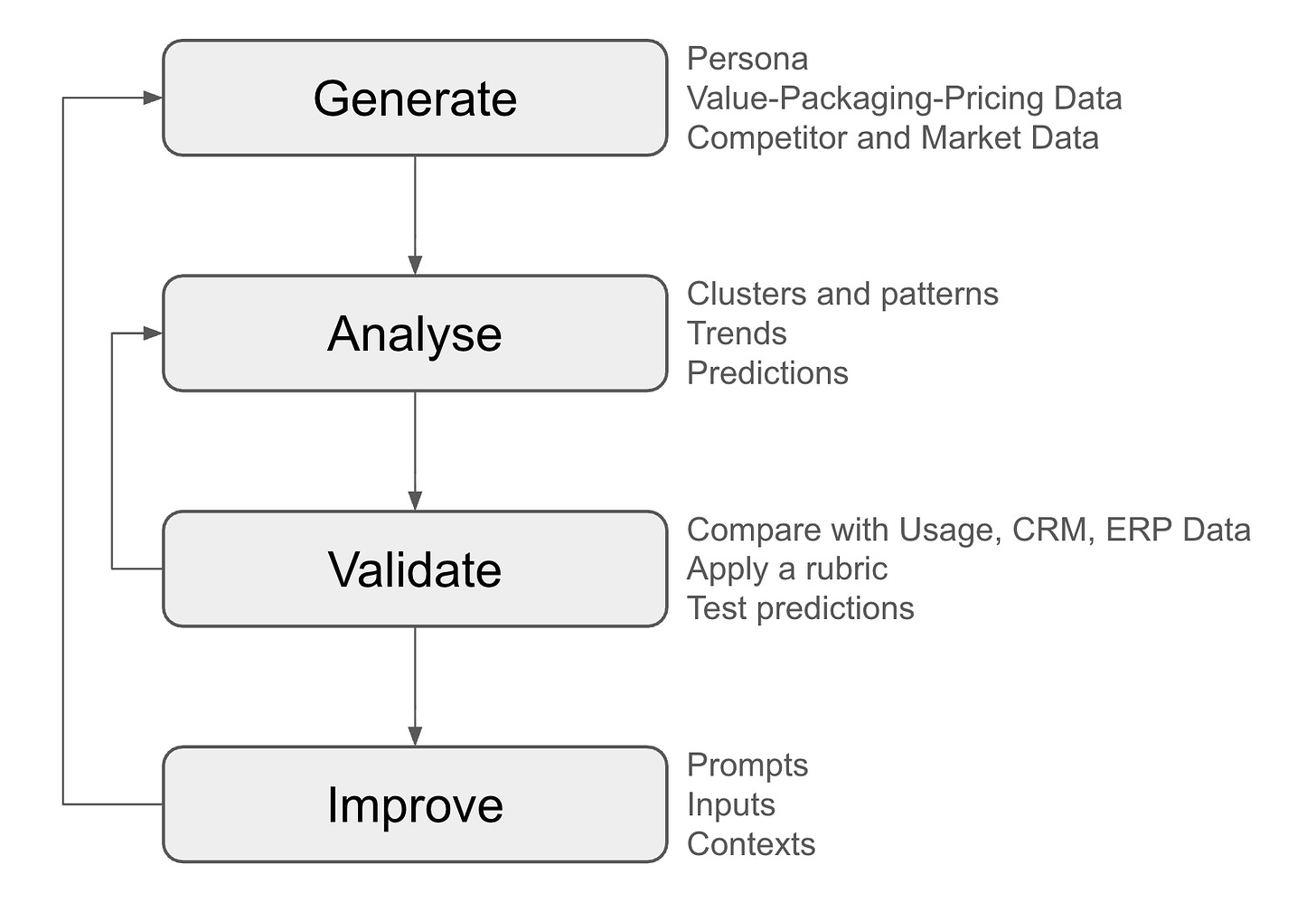

Pricing teams will operate via GAVI cycles (Generate–Analyse–Validate–Improve) on synthetic personas, model variables, and market conditions, continually tuning prompts and rubrics against CRM/ERP and qualitative research ground truth.

Synthetic data fills gaps in value and pricing models through interpolation, extrapolation and added dimensions, letting teams test value > price > cost and stress‑test different elasticity and competitive environments where real data is sparse.

Outputs include predictions, simulations and scenarios that jointly probe model behaviour, causality and edge cases, increasingly feeding both prediction and causal ML models for attribution and revenue sharing.

Fairness, transparency and explainability are core: synthetic data and explainable models form a governance loop that broadens coverage, surfaces potential harms, and makes individual pricing decisions auditable.

Strategic takeaway: the most important pricing work will happen on synthetic data before market launch, turning pricing into a lab for value creation and giving an edge to organizations that learn to think with—and challenge—these models

Synthetic data is transforming pricing. Within two years, it will become standard practice in pricing design and optimization—unlocking greater diversity in research approaches and enabling pricing models that align more closely with actual value.

Synthetic data delivers three critical capabilities: more accurate predictions, simulations of value and pricing models across multiple scenarios, and systematic testing of value-packaging-pricing combinations for different customer segments.

This will transform the pricing profession.

Why synthetic data now?

Generative AI has made synthetic data a necessary part of pricing research while at the same time made the generation and analysis of synthetic data easier.

Synthetic data is necessary because generative AI has expanded the range of the possible and accelerated development.

We can do more things (AI is opening whole new application spaces)

We can do things faster (vibe coding has accelerated innovation)

There are more and more applications, configurations, packages to price.

What we need now is better ways to explore and test value-packaging-pricing for different use cases and customer segments.

The GAVI Cycle (Generate-Analyse-Validate-Improve)

Generative AI makes synthetic data possible in four ways. With AI synthetic data is easier to

Generate

Analyse

Validate

Improve

Generate: Generate AI can be used to create virtual users and synthetic data sets.

Analyse: Generative AI has made great steps in improving data analysis and pulling in other data analysis and pattern recognition like K-means and Leiden.

Validate: AIs can then be used to validate the quality, verisimilitude, of the data which can be compared with results from actual CRM, ERP and other data

Improve: Feedback loops can be set up between generation and validation and rubrics developed to make sure that the synthetic data has predictive power (rubrics are a superpower when using generative AI in pricing)

What is synthetic data?

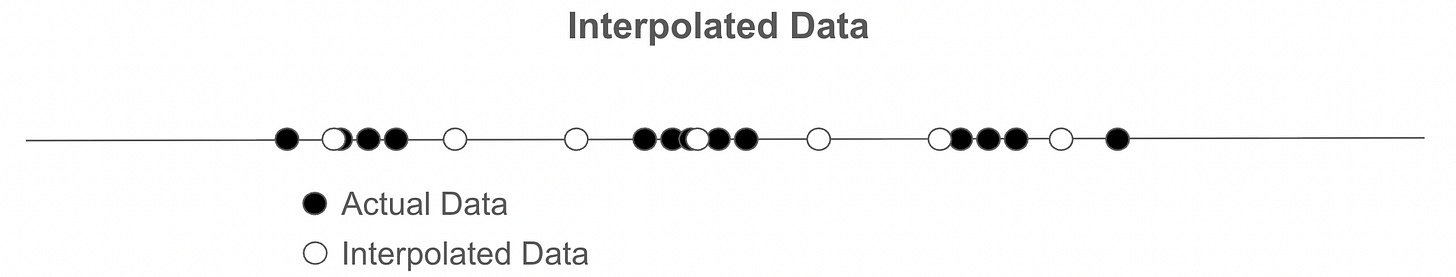

Synthetic data is data that is generated from models and other data through interpolation, extrapolation, inference or by adding dimensions.

It can be used to complement actual data (measurements of the real world) or to extend the data and data model to new situations and scenarios

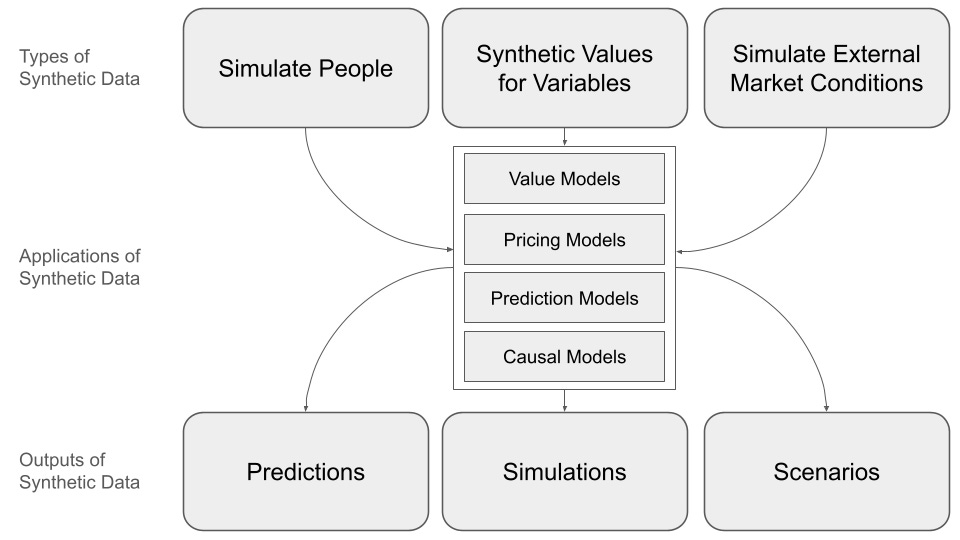

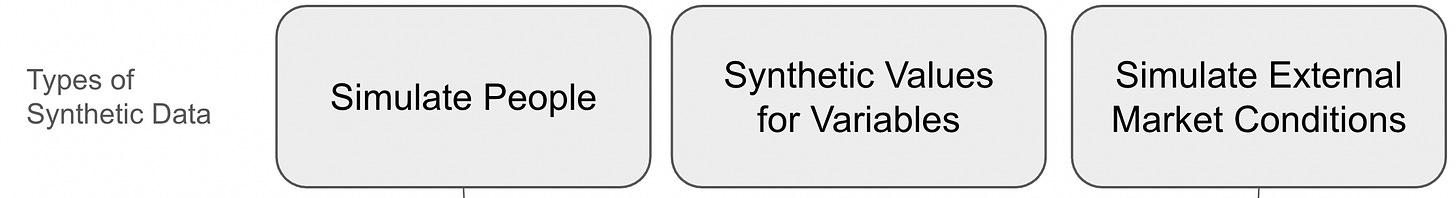

A taxonomy of synthetic data for pricing

In pricing work, the three common types of synthetic data re

Personas and virtual users

Values for variables in value and pricing models

Data simulating external market conditions

Simulating people and organization: There are a number of companies now that will create virtual users like the company Syntheticusers and this approach can easily be extended to pricing research. One can even have synthetic users participate in conjoint of Van Westendorp surveys. Qualtrics already offers synthetic panels and expect other vendors to do so as well. This approach can be taken at any desired level: individual users, the decision making unit making a buying decision, or a business unit or company. The quality of data provided by this approach is improving quickly but still needs to be validated and put into a improvement loop.

Values of variables: Pricing is model driven and the two most important models are value models and pricing models. These are both systems of equations. Equations have variables with the variables taking a range of values.

It is rare to have data available that covers all variables for the full range of interest.

The solution is to use synthetic data, interpolating or extrapolating as needed.

The synthetic data should be tested against actual data and the prompts generating the data tuned for each situation.

External conditions: The actual price that can be realized in any particular situation is often dependent on external market conditions and market dynamics. The classical pricing optimization systems (PROS, Zilliant, Vendavo and Pricefx) are very good at this within their narrow domains. One wants to be able to model many different external situations, use counterfactuals (the hypothetical outcome that a person, customer, etc. would have experienced under a different treatment or intervention than the one actually received) and explore different scenarios. Different assumptions about utility curves or price elasticity can also be included here.

The ability to test hypothetical data is central to the types of causal reasoning needed to solve some of the toughest problems in pricing like the ‘attribution problem.’

One way to think of the use of synthetic data is as a set of thought experiments that deepen are usndestanding of the dynamics and causal relations in a pricing model and how it interacts with the rest of the business system.

Dimensions of synthetic data

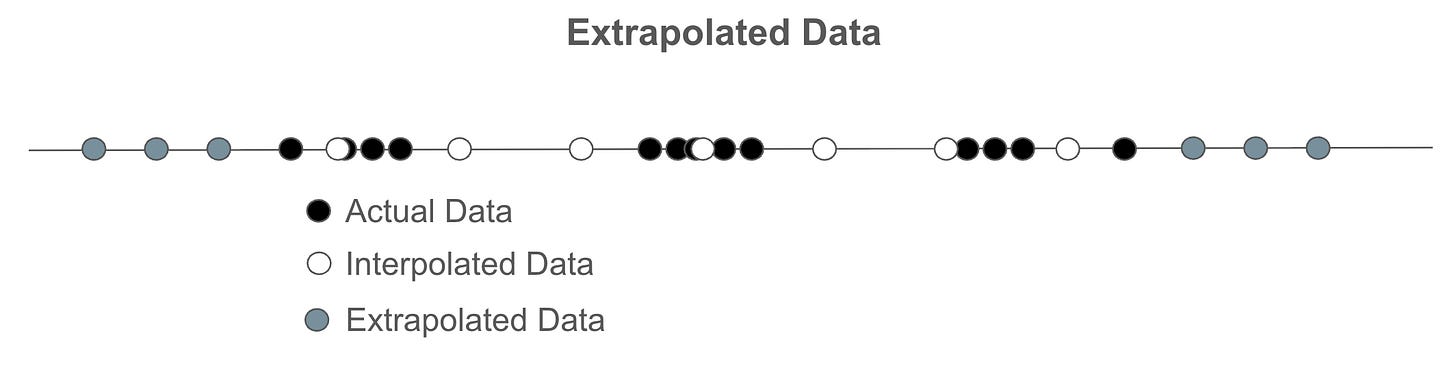

Interpolation

The most basic type of synthetic data is interpolation. Interpolation fills in the gaps in a data set. This is straightforward, provided you know what is generating the data, but you still need to be careful and ask why are there gaps? Quite often the gaps reflect underlying clustering mechanisms that can be obscured by naive dependence on interpolation.

Sometimes the data that is missing is telling you a story. See survivorship bias: “the logical error of concentrating on entities that passed a selection process while overlooking those that did not. This can lead to incorrect conclusions because of incomplete data. Survivorship bias is a form of sampling bias that can lead to overly optimistic beliefs because multiple failures are overlooked, such as when companies that no longer exist are excluded from analyses of financial performance. It can also lead to the false belief that the successes in a group have some special property, rather than just coincidence.”

Extrapolation

Sometimes one wants to test data outside the range of what is available. This is especially true when doing scaling tests. The caveats about the risks of interpolation smoothing over real gaps is even more important here.

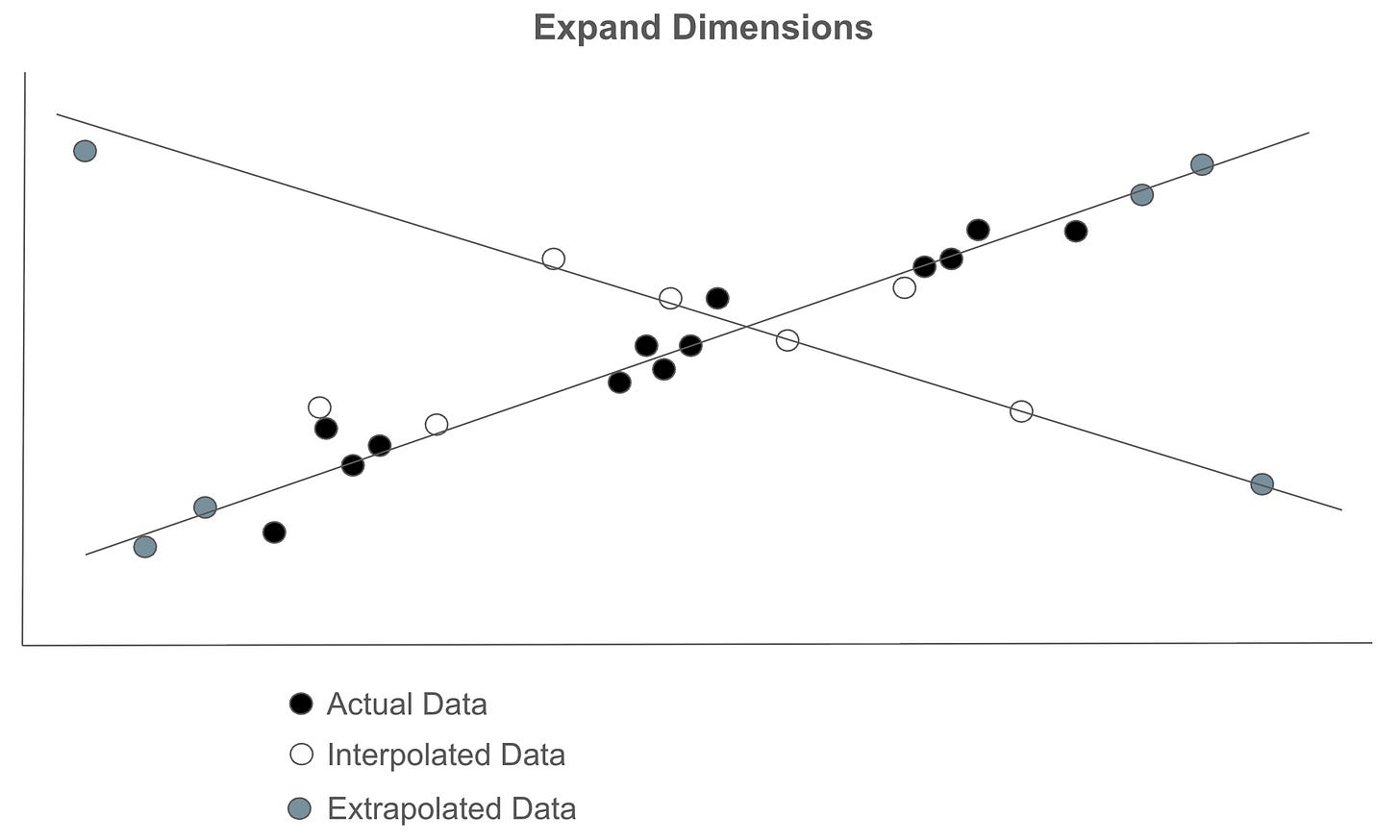

Expand Dimensions

Synthetic data gets interesting once one starts to add additional dimensions to the data. This is a technique taken directly from machine learning. One can find new patterns in data by adding dimensions.

This is a deep topic, and you will want to work with an expert data scientist when applying it. To get the flavour see “Exploring Dimensionality: Mathematical Foundations, Applications, and Impacts on Data Analysis” by Everton Gomede.

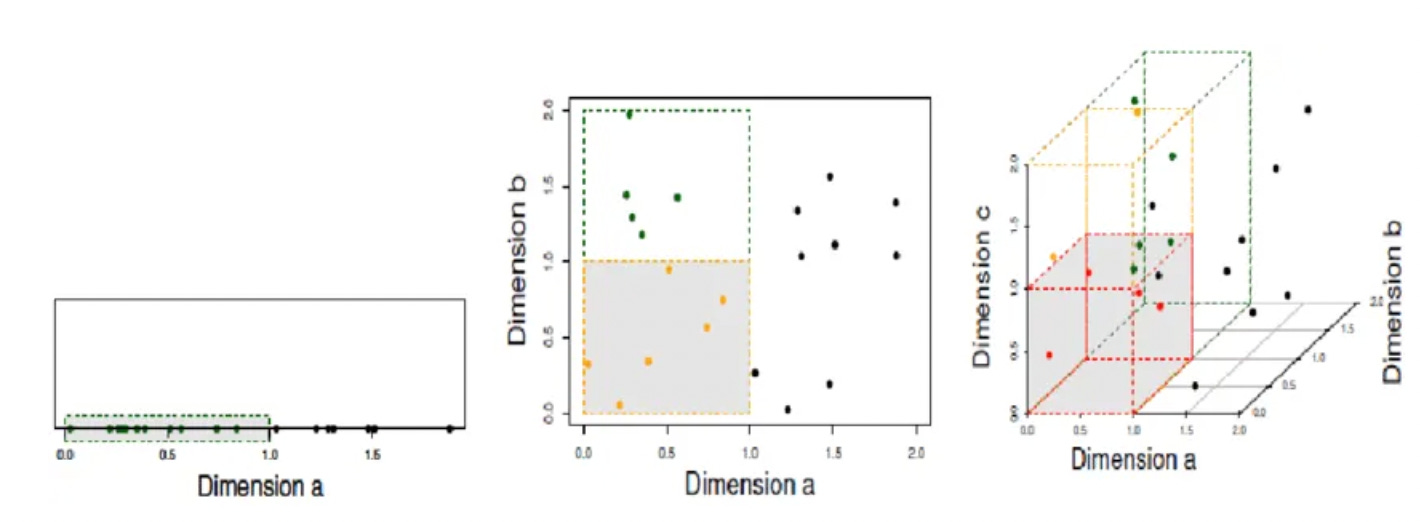

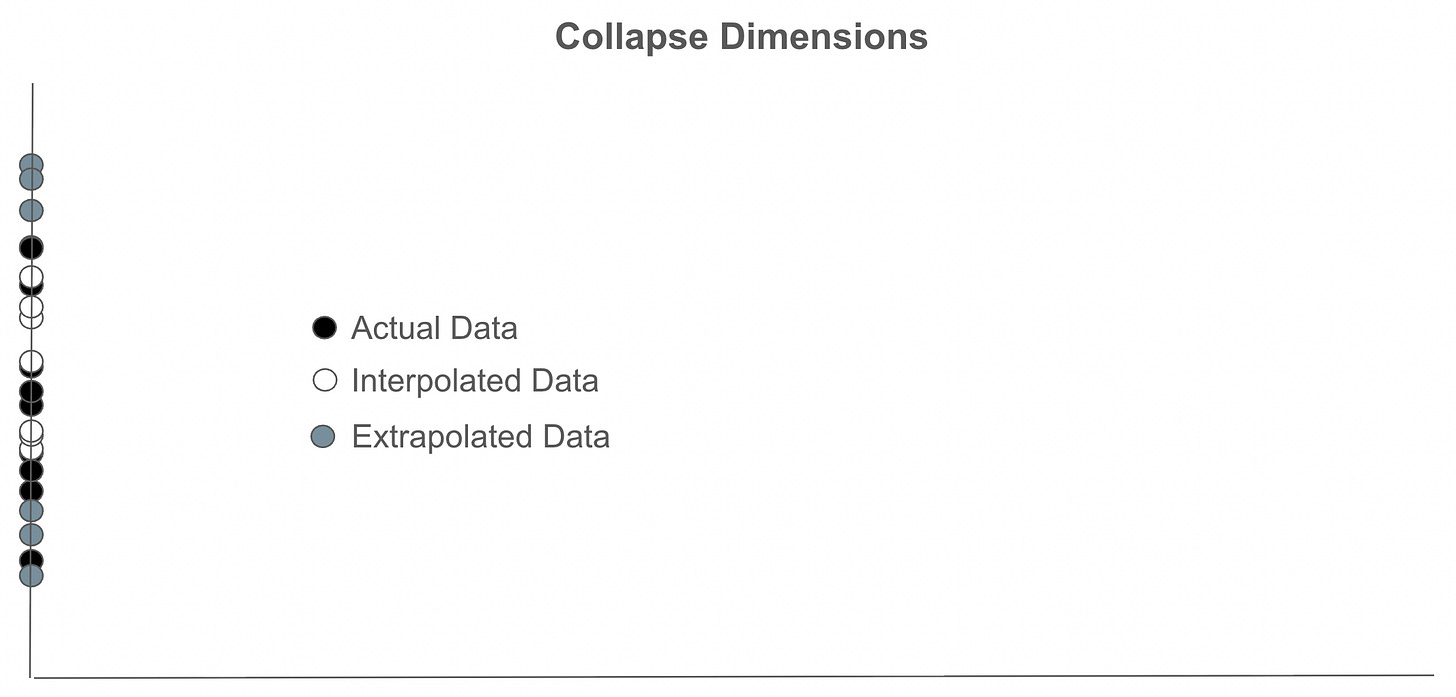

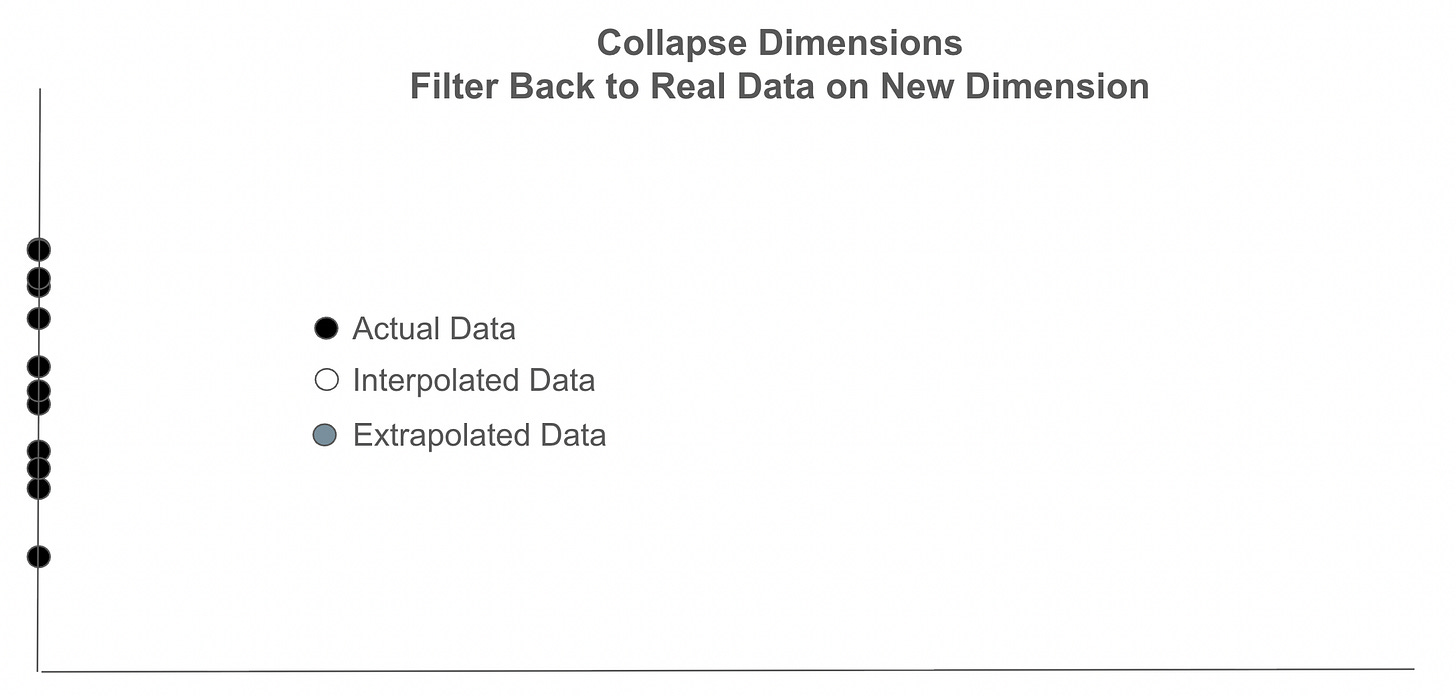

Collapsing Dimensions

Once you have added dimensions you often want to collapse the data back onto one or more of the new dimensions. This can also bring out new dimensions in the data that can give insights into how pricing is working and what is driving the observed results.

Filtering Back

Once you have reorganized your data by shifting it to a new dimension it is often helpful to take out any synthetic data and see how the actual data is distributed on the new dimension. Then ask if any new patterns are visible in the actual data itself.

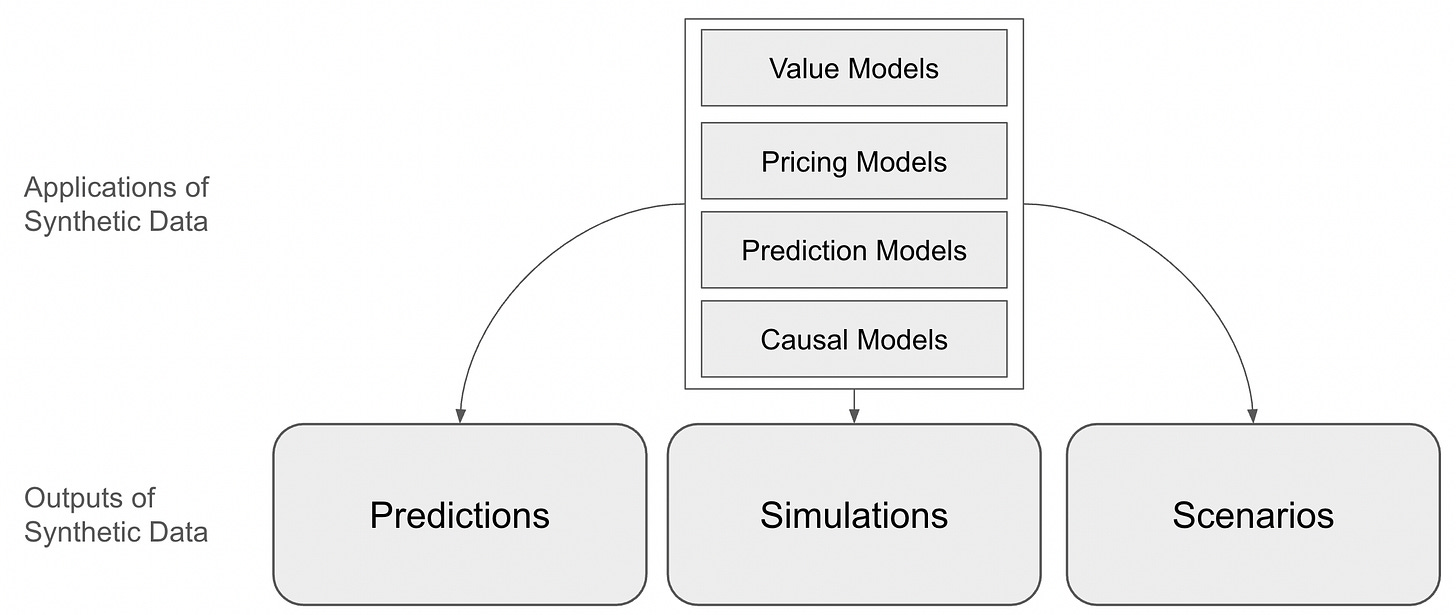

Applications of synthetic data

Applications of synthetic pricing data

In pricing work, synthetic data will be used primarily with value models, pricing models, prediction models and causal models. Down the road, we will also see synthetic pricing data used as training data for new AI models.

Value models: These models are systems of equations, the synthetic data is used to populate values for variables to test value for different companies in different scenarios. With generative AIs it is possible to get reasonable estimates for these value for specific companies.

Pricing models: Another system of equations. Generally one wants to generate synthetic data for the same ranges or companies that are covered in the value model.

Note that the best practice in pricing is to make sure that value > price > cost across different scales and in different scenarios. Synthetic data helps one do this.

Prediction models: Many pricing decisions and even pricing models themselves are dependent on prediction, and cheaper, more effective predictions are one of the core promises of AI. Recent books on intelligence, like Blaise Augery Arcas What is Intelligence put prediction at the center of intelligence. Prediction models can be fed with synthetic data and predictions made from this data tested against real world results. Prediction is an important part of the GAVI cycle (Generate, Analyse, Validate, Improve).

Causal models: Causal modelling has not yet been much used in pricing but that is about to change with the emergence of causal machine learning (causal ML). This approach is already used to great effect in health economics and outcomes research (HEOR) to understand the effects of different treatments. I will be applying this to work on the attribution problem that I am doing with Michael Mansard of Zuora and Edward Wong of GTM Pricing. The ‘attribution’ problem is how one attributes value creation in cases where multiple solutions contribute and then how one allocates that to revenue sharing.

Outputs of synthetic pricing data

Following from this, one can see that the key outputs of work with models and synthetic data are predictions, simulations and scenarios.

Predictions focus on estimating outcomes given current best estimates of conditions.

Simulations focus on exploring system behavior under rules and randomness.

Scenarios focus on contrasting different assumption-sets about the environment.

In practice, you often define scenarios first, run simulations under each scenario, and then examine the predictions those simulations produce for key metrics like revenue or profit.

Fairness, transparency and explainable AI

Whenever we are talking about AI issues of fairness, transparency and explainable AI come up. Pricing teams using synthetic data need to be aware of these issues. Synthetic data can reduce or amplify bias depending on how it is generated, constrained, and validated.

AI fairness here means ensuring pricing does not systematically disadvantage certain customer groups without legitimate justification. Fair synthetic data can rebalance under‑represented groups or enforce fairness constraints so comparable customers are treated similarly, but poorly controlled generation can simply replicate or hide historical bias.

Transparency is about making data and model choices understandable to stakeholders. In pricing, that includes clear documentation of how synthetic data was produced, which fairness goals were set, and how models were validated so that prices do not appear arbitrary or secretly discriminatory.

Explainable AI brings transparency to individual pricing decisions. By showing which factors (for example, elasticity, competitor prices, costs, segment attributes) drove a recommendation, pricing teams can check whether models trained on synthetic data behave sensibly and align with policy.

Together, fair synthetic data and explainable models create a governance loop: synthetic data broadens coverage and tests edge cases, fairness metrics flag potential harms, and explainability reveals whether model logic matches ethical and regulatory expectations. This supports more trusted, defensible pricing decisions over time.

Conclusion

Synthetic data is not a side‑show in pricing; it is becoming the main stage. Over the next few years, any team that is serious about value, packaging and price design will be running GAVI cycles on synthetic as well as actual data.

The pattern is clear. We will design value models, pricing models, prediction models and causal models together, then use synthetic data to probe them with predictions, simulations and scenarios. This is how we will explore new offer structures, new business models and new market conditions before we commit real resources and real customers.

But this only works if we treat synthetic data as part of a disciplined practice. That means validating against CRM and ERP data, tuning prompts and rubrics, and looping constantly through Generate–Analyse–Validate–Improve. It also means putting fairness, transparency and explainability at the core of pricing governance, not bolting them on at the end.

If we do this well, pricing becomes a laboratory for value creation rather than a last‑mile function that “puts numbers on” someone else’s decisions. Pricing teams will spend less time fighting for data and more time asking better questions about causality, attribution and shared upside.

My expectation is that the most interesting pricing work of the next decade will be done on synthetic data before it is ever done in the market. The organisations that learn to think with these models – and to challenge them – will define the new standards for how value is measured, shared and grown.